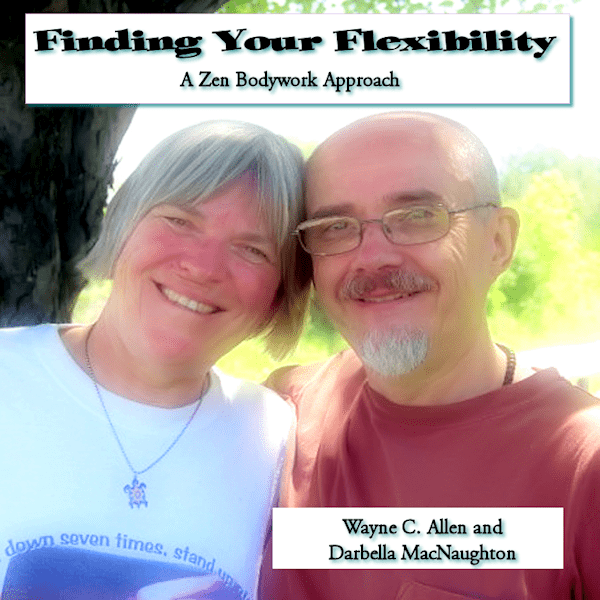

Finding Your Flexibility — Some years ago, the Worker’s Compensation Board in Ontario invited me to start working with injured workers.

Darbella and I taught them meditation, qi gong, and some yoga stretches.

We thought we were going to take the project province wide, but then the government shifted priorities, and stopped hiring outside consultants. Or something like that.

So, we had all of this material, and decided it was so good, we’d turn it into an online course. And that evolved into a pdf booklet, and online videos.

On the off chance that you might be experiencing any kind of pain (physical or mental), this course might be for you.

Check out Finding Your Flexibility here!

Here’s the introduction!

Introduction

This is the first in what will be a series of book-online video combinations. Our goal is to make Qi Gong, Meditation, Stretches and Breathwork ‘do-able’ by people beginning these practices in middle age, and by people with physical limitations. We designed this program because of a request from Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, to aid injured workers.

The Phoenix Centre’s work is always integrative, and part of “integration” is theoretical. In other words, you need to “get where we are coming from”—to understand the concepts that underlie the exercises. You don’t have to accept or believe them—just hold them loosely in your mind as you experiment with the techniques on the on-line videos.

After one seminar, a participant said, “I am really in pain. Nothing has worked, and it’s only going to get worse. Now you show up with these ideas. I can’t accept them until they work, and they can’t work until there’s a change in my body mechanics.”

I said, “Or, you could just give some of this stuff a serious effort, and see what happens.” He paused, and then said, “It can’t hurt, I guess.”

I would only ask one thing of you. Approach this process with an open mind, and actually do the exercises on the on-line videos. Read and re-read this book, and commit to 30 days of repeating the exercises. See where things are at that point. There are no guarantees in advance, other than this one:

If you keep doing what you’ve been doing, you’ll likely get the same results.

Medical Disclaimer:

In the interest of avoiding injury or mishap, any kind of strenuous physical activity conducted without the assistance of a professional coach or trainer should be discussed with one’s physician or personal healthcare advisor. The exercises and advice put forth in this book and on-line videos are by no means a substitute for medical care or expertise. Never over exert yourself. If you experience any sort of discomfort stop immediately and, if necessary, seek medical attention.

Self-Responsible Pain Management

Throughout this book, and to some extent on the on-line videos, I’m going to describe Eastern and Western approaches to living, to Bodywork and exercise, and to pain management. I want to help you see how combining these two approaches might be the smartest thing you ever did.

My initial training was in Western psychotherapy, which is often called the “talking cure.” There were body elements to this: we looked at breathing; we did psychodrama (acting out scenarios, in groups) and studied Gestalt, which has many physical aspects.

In my clinical practice, I had years of success with the “talking cure.” What I noticed, however, was that the relief tended to be mental—in other words, people gained communication skills, better understanding of their stories, and tools for talking through emerging issues. What wasn’t happening was any (or much) change on the physical level. People with great mental coping skills were still in physical pain, and things weren’t getting better with time.

I started exploring Eastern philosophies and techniques, to see if I could find something to try. I learned that there was a direct and fundamental connection between what people thought (clung to,) and what was happening in their bodies.

In 1996, I attended a 25-day program at The Haven, near Nanaimo, B.C. There, I learned a Western version of Bodywork. I learned Bodywork theory—that our bodies hold within their physical structure the story of our unresolved issues and past traumas, physical and psychological. A trained Bodywork practitioner can simply look at how you carry yourself and can thereby tell you much of your life story.

Bodywork emerged from the insights of Wilhelm Reich, a 20th century psychoanalyst. He identified what he called “character traits,” and decided that such traits were reactions to the person’s rejected (and blocked) emotions.

His idea was that people developed rigid personalities, made up of various internal stories—these stories, if left unexamined, became rigid states as opposed to flexible choices.

Reich decided that character traits were held in place by the person’s “character armour,” which is an actual tightening of the muscles of the body. He further discovered that guiding clients into their tightness, (through Breathwork and applying pressure to the body,) helped clients to break through the character armour, and from there, to begin to disassemble the ineffective character traits and stories.

So, let’s apply this to you. You might ask yourself:

“Why do I experience pain in this part of my body, and

what’s the story I tell myself about it?”

I think you might discover that there has been significant tightness in the part of your and now, this same tightness adds to the pain you feel as you work with this area. There is more happening beneath the surface than is immediately apparent.

Well, that was a bit about Reich and Western approaches. Of course, other Western tools are things like physiotherapy, drugs, and surgery.

On the Eastern side of things, Eastern methods assume that the body is filled with energy. This energy can be directed, and used for healing. You’ll hear us talk a bit about meridians, about energy (called chi or Qi,) and about how energy blockages cause the body to be “out of balance.”

In Eastern thought, our bodies are seen holistically, as BodyMindSpirit. We are designed to naturally be in balance. Internal illnesses and external injuries cause the energy to flow non-naturally, and this in turn leads to pain and inflexibility.

Pain reduction and increased flexibility are goals of this program—we assume that this will happen as the body comes more and more into balance. In other words, through specific exercises and meditation, we’ll treat the imbalance, and allow the pain and stiffness to take care of itself.

We mentioned that there are things you’d need to “get,” and here’s the first one. You will need to see how your BodyMindSpirit is right now as part of a longer ‘story’—in a sense, to accept the idea that your body is holding unexpressed emotions and traumas that pre-dispose you to be in less than optimal condition.

We call this understanding “the core of self-responsibility.” In other words,

“I am how I am, right now, because of how I thought, acted,

and dealt with my life, up to now.”

I’m asking you to look to yourself, to identify areas you have been ignoring, and to gently turn your attention to those things. No one but you can turn the tide. You’ll have to break habits and learn to think and act in a new way, but hey, the way you were doing things hasn’t exactly panned out, now has it?

The real work is always self-work.

The simplest way to begin is to have a sense of humour. Notice how you stay stuck, notice where in your body you are tight, and smile and shake your head. If you do not like how you feel or how you are thinking, change your focus and direction. In other words, no matter what, fix yourself as soon as you notice you are going off the rails.

No matter how bad a situation seems to be,

it will only change when you do.

It’s important to watch how we deal with events that seem larger than life—that we think of as “Not fair!” Gathered under this umbrella are things like death, illness, accidents, pain, suffering, global catastrophes, abuse, and the like.

When we are kids, we hear fairytales about people living ‘happily ever after.’ We believe in Santa and the Easter Bunny. Then, we grow up, and give up on Santa, fairies, and the Bunny, but seem to keep the ‘magical thinking’—if I am good, only good things will happen to me. For free. All the time.

The other side of this coin is the idea that if ‘bad stuff’ happens, the recipient must have ‘deserved it.’ It’s thinking, “Bad things only (or should only) happen to bad people.” If you hang around wakes or funeral parlors, and if the dead person died of anything other than of old age, you will hear some moron say, “I wonder why God was mad at him. I wonder what he did to deserve this.”

Being a practical, Zen person, I wonder, “Why not this person?”

What, exactly, is “fair” treatment? There is no such thing. There is just the truth of life—this happened, and this happened, and this happened.

The reality of our lives is that we live in the midst of pain, suffering, and death. No one has escaped this. Most of us will outlive our parents. Some of us will outlive our children. There will be illnesses, accidents, pain. Wondering about “why” is an attempt to avoid confronting the reality of our own sickness, ageing, and death.

There is no why. Whatever happened in your life did happen, so what’s the sense of putting energy into the “why?” thought? It’s also useless to go a step further and start assigning blame. “Someone should have done something!” This should never have happened!”

And what changes? Nothing! It still happened.

The only cure for all of this is the total acceptance of what is. From a place of acceptance, I can then choose to act differently right now, instead of just whining about unfairness.

‘The way it is, is the way it is,’ and fairness has nothing to do with it.

Pain and Suffering

Pain is one reality that touches all of our lives. For all of us, there will be the emotional pain of grief and loss. If we are injured, there must be physical pain. In every life, pain is not optional.

Suffering, however, is optional.

All suffering is self-imposed. The Buddha’s first truth is, “Life is suffering.” But his second truth is, “All suffering is caused by clinging and aversion.” In our examples, clinging is holding on to magical thinking. Aversion is the unwillingness to embrace (accept) the reality of the pain. The irony is that such aversion, clinging, and denial is crazy making, mentally painful, makes the actual physical pain much worse, and changes absolutely nothing.

One root of suffering comes from clinging to the past—wanting everything to be the way it was before the ‘bad’ thing happened. This, of course, will not and cannot ever happen, no matter how much you wish it were so. And so, you suffer.

The other root of suffering comes from imagining the future—and making that future as grim and pain-filled as possible. I won’t get into why we do this—it’s not worth the reading. This imaginary story causes us to physically tighten up and to dump a load of adrenaline into our systems—and this, in turn, adds to our pain.

In both cases, suffering comes from hating and resisting pain. Yet, the pain is real—is part of our reality.

Ram Dass once said something like,

“Life is painful; it’s like having a hot stone placed on the palm of your hand.

You have two options.

Grasp the stone tightly and burn your whole hand, or

hold the stone lightly and only burn the part under the stone. Choose.”

Most choose hardening and tightening around the pain, while adding in the “This isn’t fair” litany. And so, they suffer.

So, what is the alternative?

The Buddha’s third truth: If you let go of clinging and aversion, and live your life fully and completely, you can let go of suffering (but not pain, sickness, and death—this is not optional!)

In other words, situations do not change—you do!

I am not minimizing pain—I am simply saying that it is ‘how it is.’ There will always be physical pain, and there will always be situations that are agonizing. There will always be depraved people preying on innocents, and tragedy and death are as much a part of life a blue skies and sunsets. Bemoaning the existence of such painful situations changes precisely nothing.

Creating another way of being with the situation is always possible. The key to living life with a minimum of suffering is to hold life, and your opinions, loosely. While it is tempting to play the “It’s not fair” game, it is essential to remember that this accomplishes nothing in the real world.

The world is neither fair, nor unfair. The world simply is. Accepting this reality, as well as our ability to deal with the pain that life brings, is essential for managing your pain.

Hold the burning stone loosely.

Looking for more on this topic?

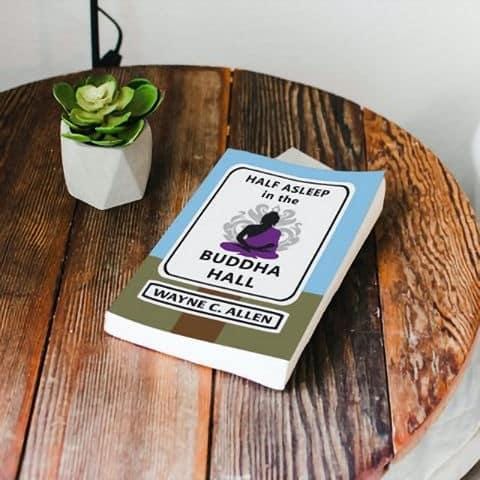

Check out my book,

Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall.

My “Eastern” book takes you by the hand and helps you to find peace of mind.

Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall is a Zen-based guide to living life fully and deeply.

(Here’s a direct Amazon link)

Purchase digital versions (Apple, Nook, Kobo, etc.) from this page