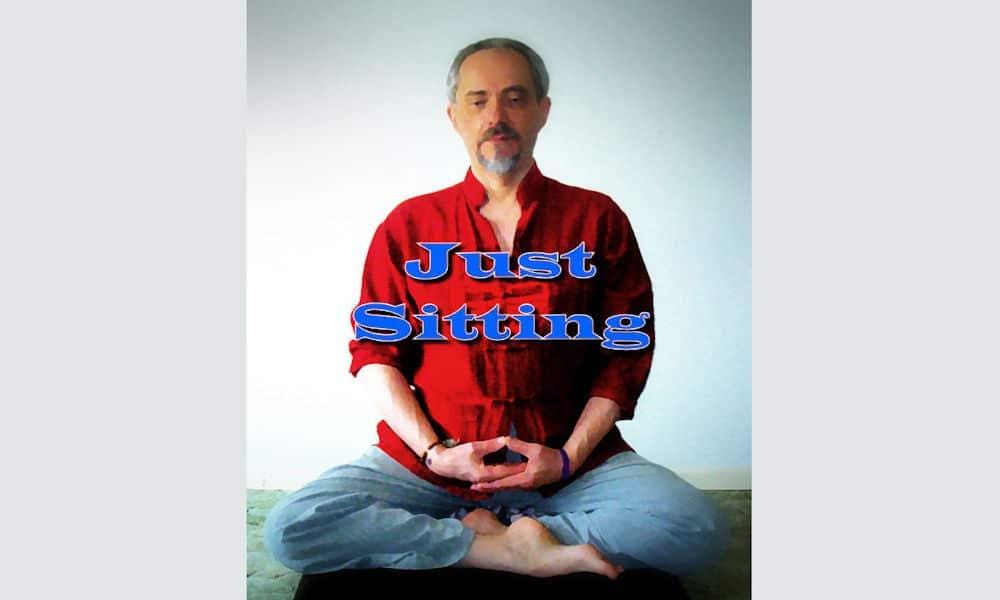

Just Sitting — a way of doing meditation that needs nothing. NO counting breaths, no mantras. Just sitting.

Want more help with things like dealing with stress, learning to combat pain naturally, meditation and Qi Gong? Check out our Book / Videos packet, Finding Your Flexibility. It’s a pdf guide, and a group of online videos.

Rather than Just Sitting, our upbringing and nature cause us to complicate our lives.

One way we do this is to assume that the stuff of life is here for us–personally. Rather than seeing ourselves as a part of something, we see everything as here for us to play with. So, for example, something simple (like meditation,) is declared to have a “point,” and that point is to be of service to me.

If you want to see this, try Googling “meditation.” What you’ll see is a myriad of organizations, ideas, and “reasons for meditating.” A simple thing has become what is described in the Tao as “the 10,000 things.”

Thanks to the Mindfulness movement, meditation has become a “tool” designed to aid digestion, reduce stress, cure phobias, and fix what ails you. This fits with the decidedly western notion that what we do ought to have a “goal.”

Which is not to make goals wrong. It’s to say that the beginning of wisdom is to be able to see that there is something else going on.

We are trained to become identified with the story we tell ourselves, and that in turn leads to us seeing everything through the lens of “me.” How does this serve me? What will I get out of it? How can I use this to my advantage?

And beneath this, almost unnoticed, is the energy in which we swim

The Taoists talk about it as an energy field from which “things” (including us!) arise. Energy becomes manifest–it is contained in the thing that arises. In the Tao te Ching, the writer uses a cup as an example:

XI (trans. Ted Wrigley)

But we use the empty space in the center

We build walls to make a room,

But we use the empty space they surround

We form a wheel to spin,

But we need the axle hole to use itThe point:

Having something is good only to the extent

That it makes nothingness usable.

Here’s part of the introductory section:

I (trans. Ted Wrigley)

What is, is, without sense or differentiation

And only divides itself into things [often trans. ‘the 10,000 things’–WCA] when we give names.Forget the names of things and you sense fit and flow

Use their names and you see uniqueness, significance

Each perspective is as true as the other.

(For more on the Tao, see my book, Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall)

The assigning of names is a human activity. The names aren’t really a problem; that comes with the assigning of categories: good / bad, for example.

The Tao tells us that names are one side of a coin, and Tao (the underlying stillness) is the other. Focus exclusively on one, and it‘s hard to see the other.

Why we meditate

Without getting into “right,” one might choose to use meditation as a way to shift gears enough to see the underlying nature of being. That was certainly meditation’s original “face.”

Things have changed.

At the start of this article, I mentioned how many different types, and places, and “reasons for” meditation there are, and it wouldn’t be hard for me to “like” some, and “dislike” other types, or styles.

That there are many types is neither good nor bad. It just is. Finding the need to judge one over the other, on the other hand, kind of takes us away from the essence.

For several years Darbella and I studied a family style of Tai Chi, and enjoyed it. Then we moved, and decided it was too far to drive to get to the class. A while later we found another school, this one an institutionalized brand of Tai Chi that shall remain nameless.

We went, and learned their short set of moves, which was different from what we knew (the order of the moves) and slightly different regarding the moves themselves. I found myself occasionally reverting back to what I knew, and this seemed to annoy the wife of the guy teaching us.

Eventually, she stormed up to me and demanded to know what I was doing there, and that I “…wasn’t allowed to teach this style, and I’m watching you!” All this judgement, both over style and substance.

Weird, as all I was doing was moving my hands a bit differently from what she was used to

This would be the “good / bad” thing, writ large. She’d made some rather strange speculations about me and my motives, and then just clobbered me with them. Labels get in the way.

Shikantaza

Shikantaza is a Japanese word that is popular in Soto Zen (a school of Zen.) It roughly translates as “only just precisely sitting.” Or, as I put it, “just sitting.” In this school of thought, just sitting is equivalent to waking up.

In other Zen schools, zazen (meditation) might be taught using props or techniques — chanting, counting breaths, doing mudras (hand positions.) In Mindfulness meditation, goals are stressed, or better, outcomes–like lower blood pressure, for example. In these cases, meditation is a tool to get someplace else.

This is done for a reason

Because of our tendency to both label and judge, it’s easy to get confused when our minds don’t do what we think they ought to do. For example, many think that the point of meditation is to quiet the mind. And when they discover how difficult that is, well, “I just can’t meditate,” or “I must be doing something wrong” pops to the fore.

So, the other meditation schools came up with techniques to distract the mind–by giving the mind something to do, like counting breaths, or whatever. They realized that, without a target, the mind is going to wander, and obsess, and story-tell, and this could lead to a not so good experience.

To toss a bit of Tao into the mix, though, wandering is what the mind does, (it is the nature of mind) so therefore, fighting it with techniques is likely doomed to failure.

Shikantaza suggests an alternative (not right or better) and that is just sitting. And observe. To see the nature of mind.

And that nature is restless, at least to begin. It’s called monkey-mind, and if you’ve seen monkeys in the wild, you’ll know that they often are restless, and moving from branch to branch.

With shikantaza, you sit, and you watch your mind. You may have an image of clouds moving across the sky. A thought arises, and, unimpeded, will drift across your mind like a cloud. To be followed by another.

A difficulty arises when we latch on to a particular thought. The story we tell ourselves about the thought takes over, and we flesh it out, playing all the roles, having a dialogue, a fight, whatever. This is monkey-mind.

Now, because we were yelled at as kids for being “bad,” the norm is to yell at ourselves for getting distracted. Then we get to have another internal fight, and declare ourselves incapable of sitting quietly. Maybe I should count breaths!

But nothing works, because this is the nature of mind.

So, what to do?

Notice. Let the thought go. Have a (non-counted) breath, and watch. And another thought will arise, and this time, maybe I can just watch it drift by.

This is the truth of Shikantaza. Mind is as it is, and resisting leads nowhere, so if I can just be with what is, I can be in the flow.

I can touch the Tao. The base. The thing that underlies the 10,000 things.

In glimpses, we we see what is there, in that dark silence. We see the nothing that makes up all things, and perhaps we see it for as long as a second or two. In that second or two, we are awake.

Bringing Just Sitting out into the world

Meditation is a tool for waking up, but it would be a pretty lame one if it only worked on a cushion.

The other day I was doing some wiring. My first discovery was that the person who had installed a light had done a dangerous job, and I started off on an internal and external rant.

Then, I realized that this was not helpful, so I had a breath, took apart the “bad” wiring, and replaced it.

Over the next hour, I found myself focussed on the myriad of wires; connecting, pulling cable, cutting, stripping (the wire, not me.)

Very Zen.

Because I was doing what I was doing, and only that. Oh, I was talking a bit too, but mostly focussed on the necessary patterns of connection.

Zen wiring.

Just sit. Find the time to watch the judgements and monkey-mind. Breathe. Let it go, just for a minute. Or a second. and see if you can see the stillness that underlies everything.

Not one better, one worse. Just to see it all, and be it all, without needing to hold on to any of it.