We get cling static whenever we find ourselves grasping onto something (or pushing it away–in which case we’re clinging on to not having it.)

Today’s topic is addressed more fully in my book, Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall.

Looking for more on this topic?

Check out my book,

Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall.

My “Eastern” book takes you by the hand and helps you to find peace of mind.

Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall is a Zen-based guide to living life fully and deeply.

(Here’s a direct Amazon link)

Purchase digital versions (Apple, Nook, Kobo, etc.) from this page

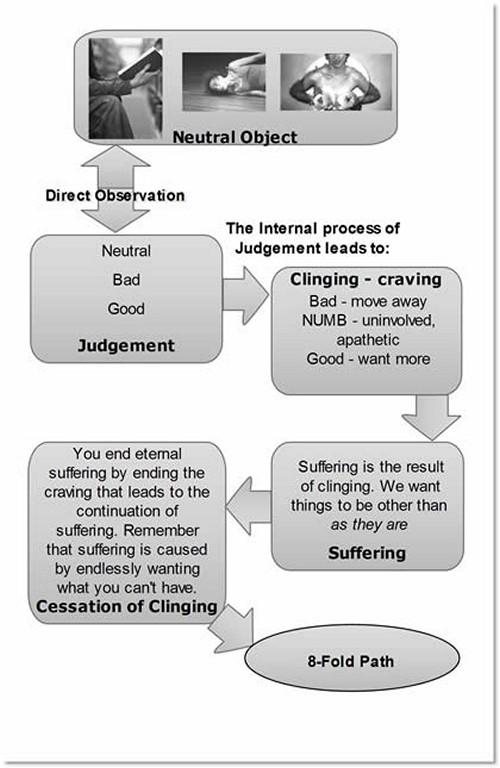

One of the earliest teachings of the Buddha concerns the nature of life, and is often called the Four Noble Truths, or perhaps more clearly, the 4 Preeminent Realities.

Or, 4 Descriptors of the way it is.

Here’s the text version of the 4 descriptors, as well as an illustration, both from the book.

1) Life, and our sense of an individual self, leads us to a feeling of dukkha, or unsatisfactoriness. Dukkha is typically translated as ‘suffering,’ but the word actually refers to anything that causes us unease.) We judge that the way life is, and the way we are, is ‘not quite right.’

2) The root cause (samudaya) of this sense of unsatisfactoriness is tanha—“thirst”—often translated as desire, or craving—which is expressed through the evil twins of clinging and aversion. Psychologists call clinging ‘the maximization of pleasure,’ and aversion ‘the avoidance of pain.’

The desire to hold on to stuff, while desiring to avoid other stuff, leads to a sensation of unsatisfactoriness.

3) The way out of this cycle is through cessation (nirodha). If I stop desiring, (through the disciplining and emptying of the mind) and live in the Now (because desire is always about wanting (or avoiding) what I had in the past, or wanting (or avoiding) something in the future), my sense of unsatisfactoriness (suffering) will cease.

4) The cure proposed by the Buddha, is magga—the Eightfold Path of ‘sound living.’

The first descriptor is typically translated “Life is Suffering,” but this English translation of the Pali dukkha misses the breadth of dukkha’s meaning. Dukkha might be thought of as pervasive uneasiness, or pervasive unsatisfactoriness. This unease can run from mild discomfort to outright agony.

If you think about it, you’ll recognize that this sense of,

“there has to be more, something else…” is prevalent

Judgement: is the expectation that

- my worldview is correct, and that

- the world “should” give a damn.

“We ask, entreat, implore, intensely desire—that the world’s objects yield abiding pleasure, satisfaction, and security. But how can they? Their fundamental nature is impermanent…” Wallis, Basic Teachings of the Buddha, pg 126‑7

Now, notice the word “abiding.” Part of cling static is trying to make things last. This is especially so with things we find pleasant, chargy, erotic, desirable. Many are the people who cry, “I want this ecstatic feeling to last!” And then they blame the thing for not listening, for not lasting. And yet, the thing we forget is that nothing lasts—not people, not circumstances, and, emphatically, not us.

Investigation, on the other hand, is expressed in my favourite word regarding relating: curiosity.

In investigation, as opposed to cling static, we look at what is, imagine what could be, and change ourselves!

A cheap illustration would be Edison inventing the light bulb.

He saw gas lights, thought about its flaws, and thought, “Hmm. I wonder what I could do to come up with another way.”

He did not stamp his feet and demand that the gas light change. He recognized an intention in himself (remember, he had no advance knowledge that he would succeed in creating an electric light) to create something entirely new. He then studied, built a workshop, and started experimenting. He learned a lot about what would not work, and eventually solved the riddle with carbonized tungsten filament.

Hopefully, you can see another blatant difference between judgement and investigation.

- In judgement, the focus, the light, is being directed to the external situation, person, or object.

- In investigation, one turns the light inward, and looks deeply at how one relates to the external situation, person, or object.

- In judgement, the intent is to force the external to change to match the internal picture.

- In investigation, one explores one’s inter-relationship between the internal and the external, with the expectation of bending the self. Releasing the self. Finding the juiciness of life in the interplay between that which I imagine and that which “is.”

Even after death, we imagine, the cling static game goes on, I’d like to suggest that there is tragedy here. What a waste! The problem is all about clinging to the image that “something better is always around the corner.”

And then, when the something better comes along, we seek something better-er. As it were.

Now, I’m not suggesting that you suck it up and stay in “bad” situations, relationships, etc. I’m saying that hanging around in bad situations with the expectation that, if you whine long and loudly enough, the situation will change, is simply absurd. It’s about accepting that I can stop making the same mistakes about situations.

Looking for more on this topic?

Check out my book,

Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall.

My “Eastern” book takes you by the hand and helps you to find peace of mind.

Half Asleep in the Buddha Hall is a Zen-based guide to living life fully and deeply.

(Here’s a direct Amazon link)

Purchase digital versions (Apple, Nook, Kobo, etc.) from this page

Most relational mistakes have everything to do with judging as opposed to investigating.

In all cases, the way past suffering (the 3rd descriptor) is in how we live and “be” (in the Buddha’s words, the eight-fold path–the 4th descriptor.)

Investigating what you are doing, and shifting from what does not and cannot work, to what allows you to drop clinging, gives you the chance to be present, to be alive, and to be aware.